For hundreds of years freedom reigned as a preeminent value in Western civilization, and with the abolition of slavery in the mid-19th century, the tide of liberty seemed destined to overpower those forces looking to hold humanity in the chains of servitude. By the early 20th century, however, this trend was quickly reversed, as governments began to exert control over ever more areas of life. Today, there is little one can do without the state, or what Nietzsche called the “coldest of all cold monsters”, either taking its cut, dictating how it’s to be done, or at the very least, watching and recording our every move.

We should not despair, however, for power still resides with the people – or so we are told. Being fortunate enough to live in democracies, we choose our leaders, and so determine our fate. But how much power does the ability to vote really give us? Major elections, especially for those who favour freedom, appear to be nothing but a choice between evils – the lesser of which is often difficult to discern. Rather than real choice, perhaps we only have the illusion of choice. Perpetual war, high taxes, mass surveillance, stifling regulation, corporate welfare, the inhumane war on drugs, and an increasing move toward censorship of those who fail to toe the statist line, seem inevitable no matter who is elected.

Those who still have faith in the system will claim that we just need to vote the right people into power – people willing to end the abuses of the state. This view, however, tends to diminish, or completely overlooks, the existence of powerful forces which make it far more likely that morally corrupt, power-hungry individuals, who favour the growth of the state, will rise to the top. The worst among us, not the best, are most likely to rule in modern democracies.

Many factors contribute to this unfortunate state of affairs, and primary among them, is the type of person most likely to enter the field of politics. For politics, like all professions, is more attractive to some people, than others. One does not choose to become an emergency room doctor if they are uncomfortable with the sight of blood, and likewise, one is unlikely to enter politics if they are uncomfortable with the nature of modern political rule. What, then, is the nature of this rule?

First and foremost, government is an institution that relies on the use, or threat of force, to achieve its ends. But while government has always been coercive in nature, the degree to which coercion, or state power, has been accepted as legitimate in a society has fluctuated over time. The West, for many years, was built around the ideal of limited government. Free markets, and other social institutions, free of the coercive nature of the state, were viewed as crucial elements in a stable and prospering society. No longer is this the case. The script has been flipped. Instead of governments being limited in what they are permitted to do, it is now the state that greatly limits what we, as individuals, can and cannot do.

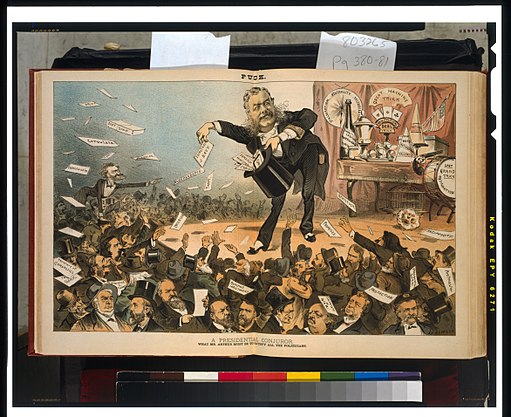

This expanded role of the state, and the immense power at its disposal, attracts, like a moth to a flame, the most power-hungry among us. Political power is unfortunately seen by many as the only power worth having, and those with the greatest thirst for power, see the state as the best vehicle for satiating their desire. It should not be surprising that most political candidates openly campaign on the expansion of the state. For state power, if victorious, becomes their power.

Not only does modern politics attract the power-hungry, but to make matters worse, it attracts power-hungry individuals of an excessively narcissistic and conceited temperament. Those who enter politics, by-and-large, “[prefer] the reign of intellect to the reign of liberty.” (Lord Acton) They are men and women who believe they should be granted the use of state power to remake the world according to their vision. Rarely is it acknowledged that what this entails is a replacement of the spontaneous order generating processes of the social world, which coordinate the plans of individuals, with a single plan devised by politicians and bureaucrats and enforced with the use, or threat, of violence.

“Why the transfer of…decisions from the individuals and organizations directly involved – often depicted collectively and impersonally as “the market” – to third parties who pay no price for being wrong should be expected to produce better results for society at large is a question seldom asked, much less answered.” (Thomas Sowell, Intellectuals and Society)

The presumption held by most politicians that they are somehow wise enough to re-order the vast complexities and emergent orders of the social world, according to their own plans, is the height of conceit. F.A. Hayek called it the ‘fatal conceit’ for when taken to its extreme, as occurred in the socialist experiments of the 20th century, it leads only to impoverishment, suffering, and death.

But while politics may be dominated by power-hungry men and women, whose conceit leads them to view all social problems as requiring political solutions devised by them, this does not preclude individuals who may sincerely wish to decrease the power and abuses of the state from entering politics. The problem, however, is that immense barriers stand in their way. Not only are most Western nations dominated by a handful of political parties who have no intention, nor incentive, to shrink the state, but these same parties control and manipulate the voting process in ways which are greatly to their favour.

Furthermore, those willing to cheat and lie in their efforts to get to the top, are always at an advantage over their more honest competitors. In the modern game of politics, truth, honesty, and integrity, do not pay. It is far easier to rally the masses around grand visions and false promises, even if such visions are impossible to implement, or would have devastating side-effects. A candidate who speaks the truth, who tries to convey to the masses the unsustainability, or destructive nature, of many government programs, is far less appealing. Reality pales in comparison to the fantasies put forth by most political candidates.

Another element of mass elections which favours the morally corrupt, is the fact that emotional appeals to hatred for one’s opponents, are extremely effective in rallying political support. This plays right into the hands of power-hungry demagogues who in their myopic quest for victory, will use any technique to win, no matter how destructive to the fabric of society. Vladimir Lenin understood the power of hatred and negativity in garnering political support:

“My words” he wrote “were calculated to evoke hatred, aversion and contempt. . .not to convince but to break up the ranks of the opponent, not to correct an opponent’s mistake, but to destroy him.” (Vladimir Lenin)

But even if a well-intentioned individual slipped through the cracks, beat the odds, and won a major election, there is the open question as to whether he could resist the corrupting influence of the modern state. For not only would the power at his disposal likely corrupt him, but he would be forced to contend with massive amounts of pressure from unelected bureaucrats, crony capitalists, and the many others who enrich themselves at the trough of state power.

While some may continue to hold out hope for a political saviour, perhaps a different approach is needed. Government oppression, or social predation in general, is at root a function of disparities in power. With a more equal distribution of power, the morally corrupt and evil elements of a society, can do far less harm. But when one group, or set of institutions, becomes far more powerful than the rest of society, abuse is inevitable – whether we live in a democracy, monarchy, or under a dictatorship.

Voting is unlikely to diminish the disparity in power created by the growth of the modern state. The past century has been full of elections, but over this same time the power differential between the state and citizen has only grown. A more effective approach for returning freedom to an increasingly unfree world, may be found through the development and promotion of technologies, and social and economic institutions, that are free of the cold hands of the state. But unless the immense concentration of power held by the few that pull the strings of government, is greatly diminished, it may not matter which of the candidates paraded before us we elect. For as H.L. Menken recognized nearly a century ago, we really only have two choices in modern democracies. We can elect a demagogue or, what Mencken called, a demaslave:

“. . .under democracy” he writes “. . .Two branches reveal themselves. There is the art of the demagogue, and there is the art of what may be called…the demaslave. . .The demagogue is one who preaches doctrines he knows to be untrue to men he knows to be idiots. The demaslave is one who listens to what these idiots have to say and then pretends that he believes it himself. Every man who seeks elective office under democracy has to be either the one thing or the other, and most men have to be both . . .No educated man, stating plainly the elementary notions that every educated man holds about the matters that principally concern government, could be elected to office in a democratic state, save perhaps by a miracle.” (H.L. Mencken, Notes on Democracy)

Lecture Two